Making Every Minute Count: Teaching Grade One in a Trilingual School

Teaching two Grade One general studies classes in a trilingual school is both a privilege and a puzzle. With exactly 680 minutes a week per class, I’m responsible for teaching Language Arts, Math, Science, and Social Studies—all while supporting children who are navigating not just one, but three languages.

The question I return to again and again is: how do we get first graders to become readers and writers with so little instructional time?

The answer lies in focus, targeted practice, and the power of research-backed programs.

Assessment and Early Intervention: A Smart Start

To ensure every child gets exactly what they need, our school uses Amplify assessments, based on the DIBELS framework, to guide our reading instruction. These assessments measure:

We conduct three major benchmark assessments each year—in September, January, and June. These provide clear snapshots of student progress and help us track growth over time.

Between these benchmarks, teachers can also use progress monitoring tools up to three times per term. This is especially helpful for students who fall below the benchmark, allowing us to keep a close eye on their progress and adjust instruction in real time.

As early as September, students who need extra support begin working with our reading interventionist. These children receive targeted instruction three times a week, focused on foundational reading skills. This early, proactive approach ensures that every child in the class receives optimal instruction, whether through whole-group teaching, small-group differentiation, or focused intervention.

It’s a carefully balanced system: high expectations, strong routines, real-time data, and targeted support—so that all our students can build the strong foundation they need to become confident readers.

The Science of Reading as Our Foundation

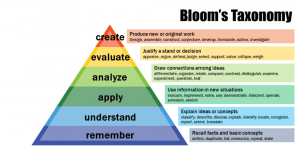

At our school, we’ve made a commitment to teaching reading based on the Science of Reading, which means our instruction is explicit, systematic, and grounded in how the brain learns to read. We use three main programs to guide our practice:

UFLI provides the backbone of our phonics instruction. Each week, I carve out daily blocks of structured literacy time that include phonemic awareness, phonics, high-frequency word instruction, decodable reading, and application in writing. These are short, focused lessons—no fluff, just the essentials, layered day by day.

Boost Reading steps in to personalize the journey. It’s our “silent partner,” giving students just-right practice that builds confidence and fluency. Meanwhile, Amplify gives me the data I need to differentiate with purpose—I know which students need more time with CVC words, who is ready for blends, and who needs targeted support with oral language and comprehension.

Making Time Work: Cross-Curricular Learning

680 minutes sounds like a lot—until you start breaking it down. That’s why every minute matters. I use center-based learning and rotating stations to allow for small-group guided reading and independent literacy practice.

But the biggest secret? Cross-curricular projects.

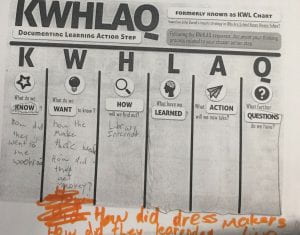

We bring literacy into math, science, and social studies. Students write observations in science journals, create labeled diagrams, solve word problems by writing number stories, and build social studies booklets that tie into our reading goals. These projects not only maximize instructional time but also spark deep engagement and real-world connections.

Reading Happens at Home Too

One of the most important parts of our literacy program is daily reading homework in all three languages—English, Hebrew, and French. This routine begins in the first few weeks of school, and children quickly settle into it. Every night, they’re practicing what they’ve learned, reinforcing decoding skills, and developing fluency.

In English, students are sent home with decodable books that directly align with their UFLI lessons. This daily practice is essential—it bridges school learning with home reinforcement, allowing students to apply their phonics knowledge in real reading situations.

But what about our fluent readers? Those students who have already mastered the basic decoding skills are encouraged to choose chapter books for homework. These might be early reader series or slightly more advanced novels, depending on the child’s level and interest. This keeps reading meaningful and appropriately challenging, while fostering independence and reading stamina.

The results? They’re amazing.

Children who came into Grade One as beginning readers are suddenly reading with confidence across multiple languages. It’s a powerful reminder that practice, practice, practice—at school and at home—really does pay off.

Writing: Building Stamina and Confidence

Our writing instruction begins the moment students start putting sounds to paper. Because handwriting is introduced in Kindergarten with Handwriting Without Tears, I can focus in Grade One on helping students connect letter formation with sound-symbol knowledge and meaning.

We write every single day—even if it’s only for 10 or 15 minutes. At the start of the year, we focus on simple sentence structure using decodable words. As the year progresses, we introduce shared writing, modeled writing, and scaffolded independent writing. Writing is integrated across subjects, too: a math story problem becomes a writing prompt; a science observation becomes a labeled diagram or descriptive sentence.

Writing: Expression, Creativity, and Purpose

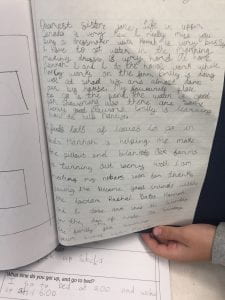

Writing is woven into our daily rhythm, starting with daily journal time. This sacred space allows children to express their thoughts and feelings, while putting all their UFLI phonics lessons into action. It’s where spelling patterns, sentence structure, and personal voice come together naturally.

We also plan strategic story-writing sessions, where students dive into the full writing process—from brainstorming and drafting to revising and sharing. These sessions help them develop as creative storytellers and build stamina, confidence, and pride in their work.

As the year progresses, we gradually introduce genre-based writing instruction to build a wide foundation of skills:

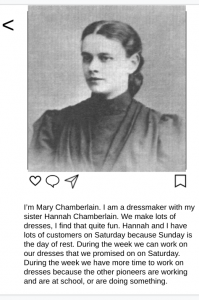

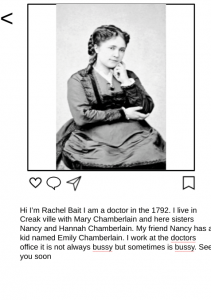

- A few months into the school year, students take on research-based animal projects. They read, gather facts, and organize their findings into short, informative pieces—often with labeled diagrams and nonfiction text features.

- In the middle of the year, procedural writing is introduced through hands-on STEM and science experiments, teaching students how to explain a process step-by-step using sequencing words and clear instructions.

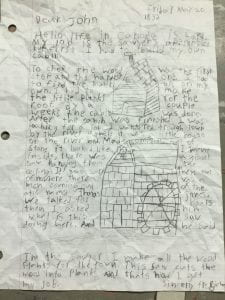

- In the final semester, we guide students through narrative writing, letter writing, and opinion writing, giving them new ways to communicate, reflect, and persuade. This gradual progression keeps writing fresh, meaningful, and developmentally aligned.

Making Time Work: Prioritizing What Matters

680 minutes sounds like a lot—until you start breaking it down. That’s why every minute matters. I use project-based learning and stations to rotate small groups through targeted instruction. While I teach a guided reading group, another group may be working on a writing task, while another is engaged in Boost Reading or word work.

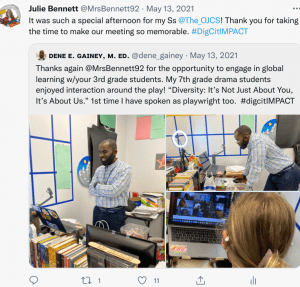

Integration is key. Science and Social Studies are taught through language—we read informational texts, we write about what we observe, we create mini-books, and we use vocabulary in context. These subjects enrich our literacy time rather than compete with it.

Final Thoughts

Teaching in a trilingual school is a gift. Our students are developing their identities across languages, cultures, and disciplines. And while time is tight, structure and intention make it possible to do deep, meaningful work. The Science of Reading has given us the roadmap. Programs like UFLI, Boost, and Amplify have given us the tools. But it’s the daily routines, the careful planning, and the belief in our students’ potential that turn those 680 minutes into a launchpad for lifelong literacy.